This blog is a reprint from one I wrote several years ago. The original appears on another of my websites.

Drunk on the Euphoria of Shared Purpose

Public opinion polls: politicians use them to hone their message; media use them to plan programming. And we – each one of us – use them, though informally and unconsciously, in order to negotiate our way through the thicket of social interaction.

Robert E. Park, pioneer researcher in the science of collective behavior, theorized that our self concept is derived from the reaction of others to our position in society. We socialize, he suggested, through a process of accommodation and assimilation. Thus, although individuals have the sense of acting independently, so much of the “I” in the social equation is subsumed by the sway of the “we”. And when one of us makes a decision about what or whom to approve, we are likely crafting decisions more from our perception of group values than we are from independent thought.

In the 2009 film District 9, a hapless Wikus van de Merwe is forced to confront the hollow myth of independent thought. Wikus is employed by a multinational company that administers District 9, a slum outside of Johannesburg where extraterrestrials have been segregated. Wikus is ordered to oversee the eviction of the aliens. As he carries out his duties he is upbeat and even cheerful. He calls the extraterrestrials “prawns” and casually destroys their incubating young. Then he has an accident and his DNA is altered.

Wikus very rapidly begins to metamorphosize into a “prawn”. As he transforms, his company decides to murder him and use his body parts for research. All of Johannesburg is warned to avoid contact with the offending citizen. Deprived of his group, Winkus must rely on himself. He becomes an “I” by necessity. He is without the affirmation or sway of the “we”, which had defined who he was and what he believed. And as an “I”, Winkus gains insight into the aliens and into his own culture.

It was Robert Park who coined the term “marginal man”. When an individual lives on the periphery of two cultures, Park explained, assimilation with either culture is not possible and marginalization occurs. While the marginal state is not a comfortable place to be, it offers the individual a unique perspective, one less inclined to be tainted by group bias.

In order to gain an undistorted view of the extraterrestrials and himself, Wikus needed to suffer a cataclysmic loss. But consumers of information today do not have to endure such privation in order to truly “see”.

This is an age of virtually universal access. Barriers that limited the cultural exposure of earlier generations have disappeared, so that ignorance of others, and of different ideas, is largely self-imposed. In order to live in a cave of narrow expectation and warped perception, one has to willfully avert the eyes from the truth.

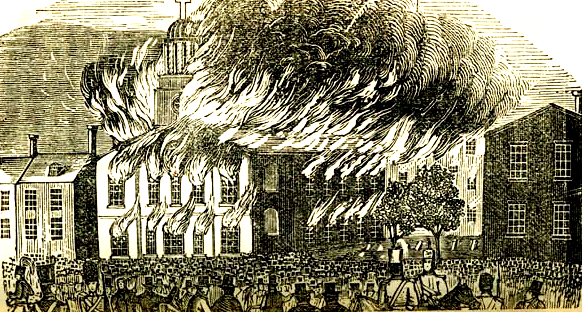

Back in 2003, at the beginning of the Iraq War, CNN and network anchors recited the government line about weapons of mass destruction. Dramatic video of “Shock and Awe”streamed through our television sets and much of the nation became drunk on the euphoria of shared purpose. Phil Donahue, on MSNBC, was a notable and vocal exception to the chorus of endorsement. He had his doubts and raised questions. He was fired. NBC claimed his dismissal was a ratings issue, though his was the highest rated show on MSNBC. Few voices were raised in his defense.

Some time later, a leaked memo revealed that NBC executives did not want Donahue to be their voice when the country was at war.

Of course, Donahue was right, and today the people who fired him sheepishly deflect blame for their complicity in the war by talking about administration lies. But the truth about the fallacy of our war effort was always there, if anyone cared to look behind the most superficial information.

Donahue is a useful and fairly recent example of how each one of us can separate ourselves from the hypnotic pull of collective conviction. It takes practice. We can begin by reading not only material that is funneled through mainline news sources – sources that dredge from a common well. We also can begin by committing to use our critical faculties, to question and look beyond our comfort zone.

And maybe we can begin on an even more microscopic level. Maybe informally, when we are in a group that is in accord about someone or something, we can suspect the legitimacy of that accord. The very fact that so many agree should make us wonder if each person in the group has independently arrived at a decision. We should question whether the people in the group – or we – are thinking, or are merely being compliant in order to accommodate the expectations of the collective will.

Resources

The Marginal Man :

http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Robert_E._Park

Shock and Awe:

http://www.dodccrp.org/files/Ullman_Shock.pdf

Collective Behavior:

http://www2.fiu.edu/~westl/Lecture%20Notes%20pdf/Collective%20Behavior.pdf

Military Cost of Iraq War:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Financial_cost_of_the_Iraq_War

and

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/09/03/AR2010090302200.html

By A. G. Moore